It’s easy to assume that the technology we use today is used because it is the best option available at any time, but surprisingly, that’s not always the case. The modern personal computer is just one example of an endless array of possible end results; we continue to use it largely because it is familiar and widely supported, not because it’s the best at every task.

The process of a technology becoming dominate because of the sheer force of its popularity is known as lock-in (check out the book You Are Not A Gadget for more). Take Windows XP as a recent example; despite being succeeded by two new generations of Windows, each of which offer superior security and features, Windows XP remains popular. Businesses are forced to continue using XP because they’ve developed a tangled mess of systems and programs that they’re afraid of breaking. Individuals often choose to use XP because it’s familiar, or because they own older hardware and don’t want to upgrade. But whatever the specific reasons behind each individual decision to continue using XP, it’s a perfect example of lock-in.

Once this entrenchment has set in, it’s extremely difficult to turn back the clock. But it isn’t impossible; it can occur when a new type of technology threatens to supersede an existing one. That’s exactly what’s happening with smartphones right now. It’s a chance to hit the reset button, and the consequences will be – let’s say, interesting.

It’s easy to neglect the trees for the forest, and vice versa. When we talk about the modern personal computer, we must also recognize that it is not merely a class of device, but an industry. Some of the largest companies today – such as Microsoft, Intel, and Hewlett Packard – are rooted in the computing industry. A change to the personal computer doesn’t just mean a change to a specific device in our homes. It means a change to these companies, a change to how we use technology in our everyday life, and a change in how technology reflections on us as individuals.

If anyone has their finger hovering over the reset button, it’s Apple. This darling of Silicon Valley fought the good fight, but ultimately lost completely, keeping out of bankruptcy court only because of investor dollars and the re-hiring of the company’s exiled CEO, Steve Jobs. Apple failed as greatly as any company can fail without being erased from existence; but today, it’s outrageously successful. Not because it unleashed a new smartphone, but rather because it unleashed a new computing experience.

Everything about the iPhone was different from the personal computing paradigm that has been locked in. The operating system, iOS, is original. The hardware does not rely on Intel, but instead is based on a custom design using the ARM instruction set. The method of user interaction is entirely unlike a personal computer, as is the form factor. Yet, despite this, it does most everything you expect for a PC; it runs applications, it allows access of online content, and it plays media.

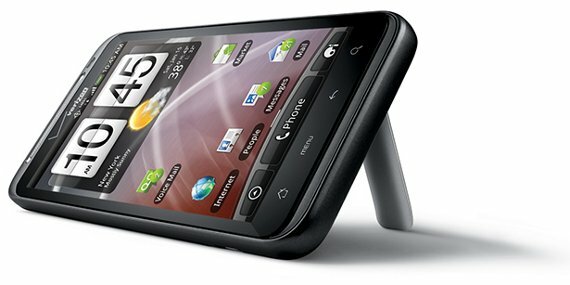

Of course, the same things can be said for all modern Android phones and most new tablets, as well – and that’s the point. Smartphones (and their new big brothers, tablets) are doing most of what a computer can do, but doing it differently, and doing it outside of the companies and software usually associated with the PC.

I’m not saying that the PC will die. But what I am saying is that the next ten years are going to see a great disruption in the consumer tech industry, and it will likely rearrange many long-standing assumptions. Windows may no longer be the most popular operating system; Intel may not longer be the world’s most illustrious chip maker; the home desktop may disappear, consumed by dockable phones.

Predicting the results is difficult to the point of impossibility (in my opinion, at least), so I will not try to make any grand pronouncements here. What I can say definitively, however, is that the smartphone is the most important consumer electronics device released since the personal computer. The reset button has yet to be hit, but it’s there, and I think we’re only a few years from seeing its use.

You must log in to post a comment.

{ 1 trackback }